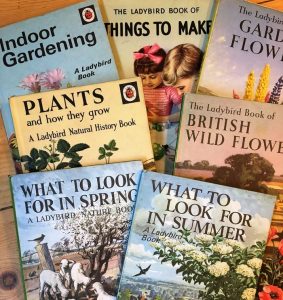

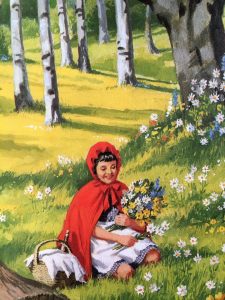

So many of us will have grown up with Ladybird books at school in the 1960s and 70s that it's hard to remember that they weren't always a fixture on school shelves. The school market certainly wasn't in the minds of the company when the Loughborough printers, called Wills & Hepworth, first began publishing children's books. The first classic Ladybird books, which came out in the 1940s, were fiction and designed for pre-school children, with rhymes about animals, Nursery Rhymes, ABC picture books and re-tellings of traditional tales such as Dick Whittington.

|

| The large prototype book, with overlay down over Margaret's illustration. Also the small prototype and the final book |

What's more, in the 1940s, publishing children's books was seen as a sideline to the core business of Wills & Hepworth, who focused on local commercial printing, among a diverse range of other activites. There was even some talk in the late 1940s of ceasing children's book publication altogether, to concentrate on printing for the burgeoning Midlands car business. Yet within 15 years, everything had changed. Ladybird was firmly established as one of the biggest players in children's publishing and the books could be found in almost every school and library and a great many homes as well. So what was it that led to this abrupt change in direction and in fortunes?

On his return to Wills & Hepworth after his war service, employee Douglas Keen was given the minor area of 'Ladybird books' to look after.

Travelling the country as a salesman and speaking to many different wholesale book-buyers, Keen realised there was a gap in the book market for well-made, robust and colourful books in schools. He felt the Ladybird format could meet this market well and tried to convince the board that they should increase the age-range of publications and focus on non-fiction. But his ideas fell on deaf ears. Children's book publishing was still seen as a sideshow, Keen as enthusiastic but misguided, and the company went on as before. Keen persisted - motivated not only by his vision and belief in the importance of good educational materials for all, but by the pragmatic requirement to secure and further his career.

|

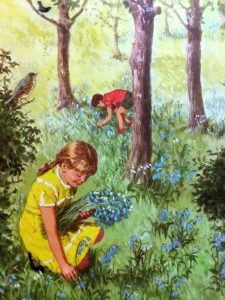

Keen wrote the text, his mother-in-law produced the illustrations and his wife produced the vignettes

|

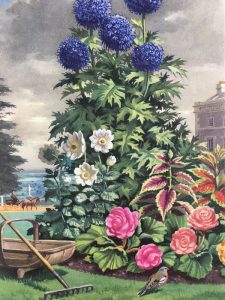

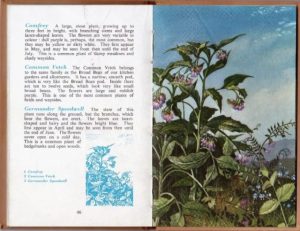

He chose a topic that interested him - British Birds - and wrote the sort of book he had in mind, with each page devoted to a different bird.

His mother-in-law, Margaret Jones, was a talented amateur water-colour artist and she created the plates for the facing page. His wife, also Margaret, shared the artistic talent and she created the small vignettes for the text page using ink and scraper-board. This book was much larger than a standard-sized Ladybird so a separate version was produced in the the classic small size.

The resulting book was shown to the board - and this time it convinced them. British Birds and Their Nests was commissioned, written by Vesey-Fitzgerald and illustrated by Allen Seaby. It was a huge success. More nature books and non-fiction books swiftly followed. Ladybird's commercial success began to take off in spectacular fashion. Quickly other aspects to the business were dropped and Keen's own star also rose sharply. He was soon appointed to the board and within a short time was responsible for commissioning all titles from then until the sale of the company at his retirement in the mid-1970s.

So an inconspicuous item at first glance - but with quite a story to tell.