|

| Back in 1941 Puffin Picture Books published a book on the Battle of Britain. It also contained beautifully stylish and evocative illustrations |

This to some extent reflects the spirit of the age - of the 1950s to 70s - to look forward, not backwards, towards a constructive, technology-driven future. But probably a bigger influence was the perspective of Ladybird's editorial director, Douglas Keen. As a humanist and a pacifist he was reluctant for the books he commissioned to dwell on 20th century warfare - and certainly not to glorify it.

|

| The new Ladybird Expert books |

This is a matter I discussed in a post I wrote three years ago: "What to Look for in Vain"

In the post I discuss the topics that Ladybird, rather surprisingly, never covered. Now that Penguin-Random House have bought out their new Ladybird Expert series, it will be interesting to see how many of these gaps are eventually closed. For these reasons I was particularly looking forward to reading the latest Penguin-RH publications: The Battle of Britain, by James Holland, illustrated by Keith Burns; and Shackleton by Ben Saunders, illustrated by Rowan Clifford.

I read them both this weekend - and I was not disappointed.

Let me start with The Battle of Britain. The premise of these new Expert books is to take topics that adults will be interested in finding out a little more about and to present the content 'old-school'. The small size and traditional layout of a Ladybird doesn't just lend itself to children's reading material but also for all of us who want more than bite-size information but less than a traditional book or densely packed website. For me the format works really well (and I talk a lot more about the format and concept here).

|

| Left: new artwork by Keith Burns. Right: a rare WW2 illustration by Frank Hampson, 1968 |

The Battle of Britain is a topic I felt I didn't know enough about. I've picked up bits from school, from old films, from Biggles (!) and from the odd documentary. This book collated the odds-and-ends in my head, sorted them out, added new stuff, gave the whole lot a context and then sent me on my way. It was an excellent read. Really very good. For different reasons it stands with 'Quantum Mechanics' as my favourite so far.

The first thing I have to single out is the artwork. Keith Burns' artwork is simply wonderful. Although not exactly vintage Ladybird in brush-stroke, it is vintage Ladybird in spirit. It does what the best LB artwork always did: it takes at least its fair share of the story-telling.

The first thing I have to single out is the artwork. Keith Burns' artwork is simply wonderful. Although not exactly vintage Ladybird in brush-stroke, it is vintage Ladybird in spirit. It does what the best LB artwork always did: it takes at least its fair share of the story-telling.I'm not a historian - except perhaps of Ladybird - so I can't really comment much on the accuracy and originality of the content. But it seems to me that writer James Holland manages well the need to spin a thrilling yarn with the need to give a balanced account. Now when golden-age Ladybird history writer L. du Garde Peach was recounting most of the original 'History series' books he was writing at a time when history for children was more closely related to story-telling than it was to history for adults. It was thought that engaging a child's imagination was more important than absolute historical accuracy (and thinking of all the 'proper' historians today who ascribe early inspiration to this series of books, I feel this may be a good point).

Be that as it may, I can imagine that when writing for children or adults today there is pressure to represent a balance of view-points - an imperative which rarely got in the way of Capt. WE Johns or L du Garde Peach. One of the ways that Holland does this is by weaving in extracts of testimony from pilots on both sides of the conflict. He also sacrifices the (surely tempting) 'plot device' of stressing how close Britian came to losing the conflict. Indeed, it seems to me that he makes a point of the difficulties inherent in the German offensive and reminds the reader to see beyond the idea of the plucky little island holding out against overwhelming odds.

And this is where I come back to the artwork sharing the story-telling. Whilst the writer restrains from over-playing the drama, the artist brings all the thrills and exhilaration and colour he can to animate the tale. The writer quotes first-hand testimony from pilots; the artist sweeps you up in the air, sends you soaring and then drops you in a spin, makes you almost sea-sick on the high seas and scorches you in the fires. Whilst writer Holland avoids a glib ending to the conflict and reminds us that the war, at this point, was only just beginning, it's left to the artist to tell the story of a homecoming, a grateful people and, if you like, a happy ending, all in one last stirring picture:

As I've sometimes remarked before, Douglas Keen possessed a remarkable skill in matching writer and artist to commission. On his occasion Penguin-Random House have done the same thing very well indeed.

|

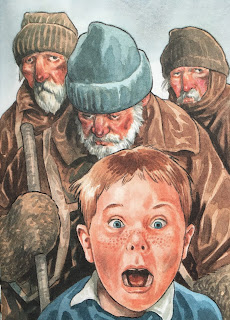

| Rowan Clifford, Shackleton, 2017 |

|

| John Kenney, Captain Scott, 1963 |

The artwork is skillful but I think the problem is that the artwork doesn't pull its weight in the story-telling. The pictures often seem to be there to take up their allocated space, not to advance or add depth to the story. The whole book, probably unfairly, suffers by direct comparison with the vintage Ladybird classic Captain Scott. In 'Shackleton' I miss the light and energy of Kenney's original artwork. As Shackleton's party were often short of light and energy themselves in the Antarctic winter, you might say that the artist captured a truth - but this doesn't enhance the pleasure of the reader.

Where the artwork is most successful, as in the following pictures, it draws you into the scene and adds depth to the text.

Sometimes, however, it did less than it could have done to help me empathise with the characters' ordeal or to add structure to the story-telling.

A few final points

1) I started this post talking about the gaps in the topics covered by vintage Ladybird. One of the biggest gaps in the history books particularly is the lack of coverage of women: female figures and women's achievements get very little coverage. Times have changed a lot since Keen was commissioning new books but I'm surprised Penguin-Random House chose not to ring these changes from the start but instead reached for the safest of Boys Own topics. Ok. It's not a problem, as long as they get their act together quickly. With this in mind, my top suggestions for history books would be:

- Ada Lovelace

- Life and times of Jane Austen - yes a quiet domestic life but what turbulent times she lived in! most of which find echos in her books. Plus the bicentenary of her death is coming up fast.

- Female aviation pioneers

- The Suffragettes

- The Brontes

- The Empire - perhaps an attempt at an honest look at Britain's imperial past

2) I hope, going forward, Penguin RH think hard about matching artist with commission. When they find the right artist, one capable of sharing the story-telling with the writer, I feel they should give that artist equal billing. Although the names of the creators are never on the cover of a vintage Ladybird Book, on the title page artist and writer, quite rightly, share the credit equally.

Artwork was at the heart of vintage Ladybird success and for this new project to flourish longer term the same needs to be true today.

3) Quibbles aside, the books are excellent. Hope you enjoy them too.